The Shenzhen Precedent: How China's 5-Year BCI Plan Could Shape Neurotech's Future

I spent last week in Shenzhen while speaking at the Blender Conference.

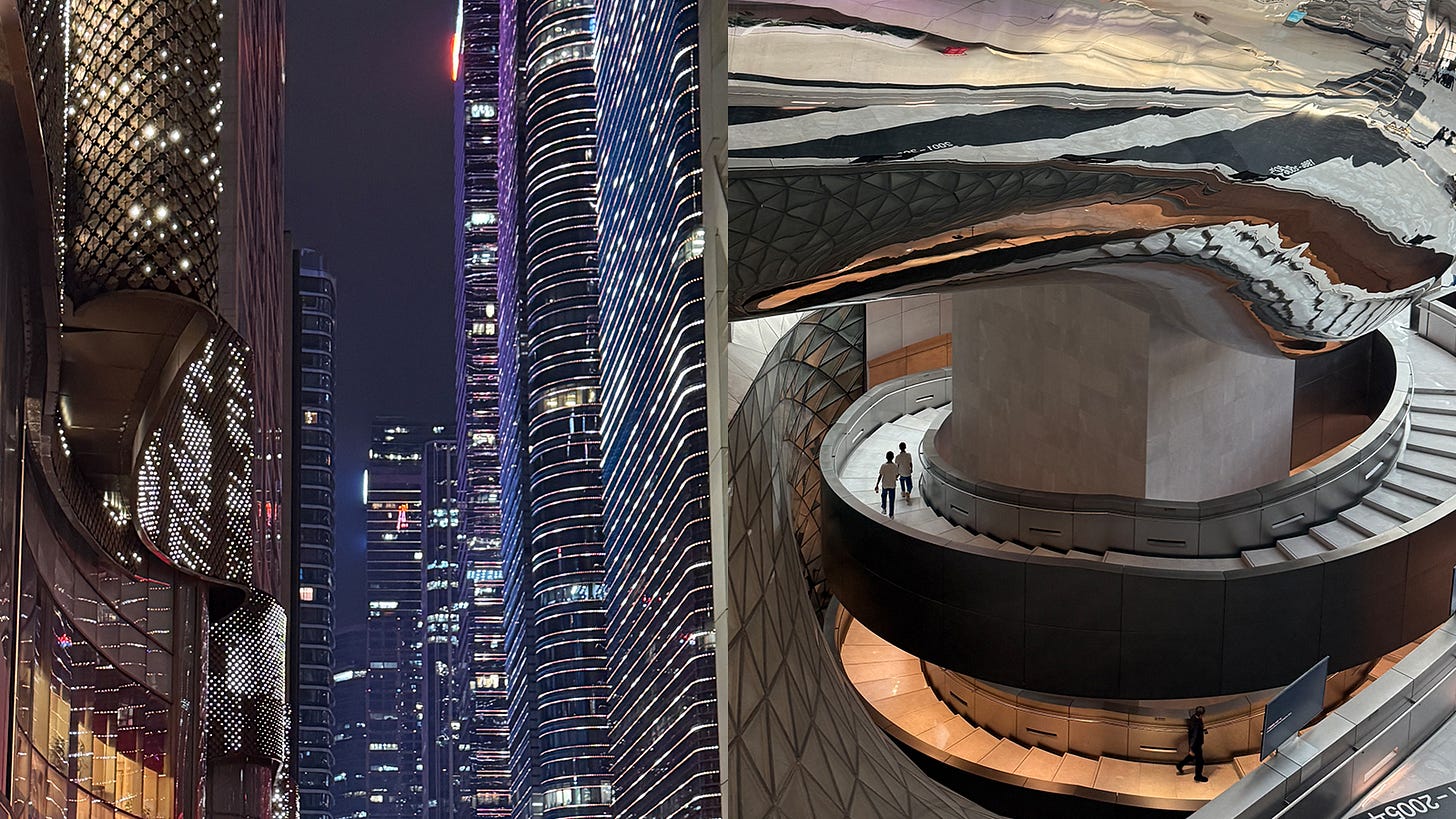

The city is overwhelming. Eighteen million people packed into a space that was farmland and fishing villages forty-five

years ago. GDP north of $500 billion. Robots delivering room service to my hotel room, driverless taxis and drones buzzing everywhere. Skyscrapers that seem to multiply overnight. You walk through the electronics markets in Huaqiangbei and realize this is where the world’s hardware gets born.

Shenzhen didn’t happen by accident. It was designed.

In 1980, the Chinese government picked this sleepy border town and turned it into the country’s first Special Economic Zone. They gave it special rules, tax breaks, and told it to experiment. The result is the most concentrated tech manufacturing ecosystem on the planet.

Now China is doing it again. This time with Brain-Computer Interfaces.

How Shenzhen Actually Worked

The story we tell about Shenzhen is usually about speed and scale. A fishing village becomes a megacity. True enough. But the mechanics of how it happened are a lot more important than the mythology.

The Chinese government didn’t just cut taxes and hope for the best. They built an entire industrial stack from the ground up. Foreign companies got exemptions on import duties. Local firms got access to cheap land and streamlined permits. The Shenzhen government actively recruited talent from across China, even bending the hukou household registration rules to let migrants access local services. This was radical. It meant millions of ambitious people flooded into the city looking for opportunity. Infrastructure followed: dense network of component suppliers, contract manufacturers, and logistics providers that make hardware production possible at speed. A startup in Shenzhen can go from prototype to production run in weeks. The supply chain flexibility is unmatched anywhere in the world.

The government also tolerated things that would have been shut down elsewhere.The early days of Shenzhen were full of shanzhai, copycat manufacturing. Controversial, yes. But it lowered barriers to entry and let thousands of small firms learn by doing. Over time, those copycats became innovators. Today, Shenzhen files more international patents than any other Chinese city. Huawei alone published over 37,000 patent applications in 2024.

The rise of Shenzhen is far more than just free-market magic. It is definite intent backed by industrial policy executed with precision over four decades.

China’s 2025 BCI Program Follows the Same Script

In July 2025, China’s Ministry of Science and Technology released a document called the Implementation Opinions on Promoting Innovation and Development of the Brain-Computer Interface Industry. The title sounds very bureaucratic, but the content shows another ambitious blueprint.

The plan sets hard targets. By 2027, China aims to achieve breakthroughs in core BCI technologies like electrodes and chips. By 2030, the goal is a mature industry with two to three globally dominant companies and a full ecosystem of specialized firms. The language is identical to the Shenzhen playbook: build the stack, nurture champions, capture the market.

Regional governments are already moving in line with the initiative. Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangdong province, where Shenzhen is located, have each released their own BCI action plans. Shenzhen itself is a focal point, leveraging its existing hardware expertise to move into neural interfaces. The same infrastructure that builds smartphones and drones will now build brain implants.

The numbers are small today. China’s BCI market is projected to be in the $500-600 million range for 2025. Small, but the trajectory is clear. This is early-stage Shenzhen all over again. The state provides the vision, rules and the capital. The regions compete to execute. The firms that emerge will have the full backing of the Chinese government behind them.

What This Means for the West

Morgan Stanley projects the US BCI market could reach $400 billion by 2040 within the medical space alone. Globally, the numbers are larger still. This is the next major computing platform. The interface layer between human thought and digital systems. Whoever controls the standards for this technology controls access to the most valuable resource in any economy: the neural networks of its constituents.

Right now, the West leads in BCI science. Neuralink, Synchron, Precision Neuroscience, these are some of the companies pushing the boundaries of what’s possible. But scientific leadership and industrial dominance are different things. The US invented the solar panel. China manufactures 80% of them. The US pioneered semiconductor design. The most advanced fabs are now in Taiwan and South Korea, vulnerable to geopolitical shocks.

The pattern repeats because the West has forgotten how to think about industrial strategy. We celebrate individual entrepreneurs and breakthrough innovations. We do a little less well at building ecosystems and securing supply chains. China does both.

The BCI industry is fragmented. Over 100 companies worldwide, most with less than $50 million in funding. Only three have reached unicorn status: Neuralink at $9.6 billion, Australia’s Synchron at ~$1 billion (including a recent investment from the Australian Government) and Switzerland’s MindMaze at $1.5 billion. There is no dominant platform yet. No agreed standard. This is the window of opportunity, and it is closing fast.

In 2025, the industry saw three seismic shifts. Apple released a new interface standard for “thought as input” in May. OpenAI’s Sam Altman announced Merge Labs in August with a quarter-billion-dollar war chest. A month later, Meta began shipping neural wristbands for its AI glasses. The commercial era of BCIs is about to begin. China’s entry as a state-backed industrial force raises the stakes dramatically.

The Choice Ahead

Western governments face a decision. Continue with the current approach, market-led and fragmented, and risk losing a critical technology platform. Or learn from Shenzhen and build a strategic blueprint now.

The West has many strengths China lacks: open innovation ecosystems, strong intellectual property protections, democratic values that can shape ethical frameworks for neuro-rights. The goal is to create a Western industrial strategy that leverages these advantages while addressing the weaknesses.

This means public investment in advanced BCI research. It means partnerships between government, universities, and private firms to de-risk long-term development. It means securing supply chains for critical components. It means establishing firm legal and ethical standards for brain data that can become the global benchmark.

It means regulation concurrent with innovation – not postpartum.

Most of all, it means speed. Shenzhen took forty years to build. China’s BCI program is working on a five-year timeline. The West cannot afford a decade of debate while the future gets built elsewhere.

As I write in my upcoming book Neuraleap, the brain will become the biggest market there is. The entities that shape this market will wield influence over human experience at a scale we have never seen. The time for nations to step up and help design the blueprint for a neural future is now.